Importance of agri exports — and what Govt can do to boost India’s farm trade surplus

India’s agriculture exports have grown 16.5% year-on-year in April-September, and look set to surpass the record $50.2 billion achieved in 2021-22 (April-March).

Interestingly, even commodities whose exports have been subjected to curbs — wheat, rice and sugar — have shown impressive jumps in shipments.

The government had, on May 13, banned the export of wheat. Yet, according to Commerce Ministry data, wheat exports, at 45.90 lakh tonnes (lt) during the April-September period, were nearly twice the 23.76 lt for the same period last year.

On May 24, sugar exports were moved from the “free” to “restricted” list. Also, total exports for the 2021-22 sugar year (October-September) were capped at 100 lt. On September 8, exports of broken rice were prohibited, and a 20% duty slapped on all other non-parboiled non-basmati shipments.

Despite these measures, non-basmati exports have risen from 82.26 lt in April-September 2021 to 89.57 lt in April-September 2022, alongside that of basmati rice (from 19.46 lt to 21.57 lt). Sugar exports, likewise, grew 45.5% in value terms to $2.65 billion during April-September, and are on course to exceed the all-time-high of $4.6 billion reached in the 2021-22 fiscal year.

The impressive growth in exports is, however, offset somewhat by imports that have surged even more.

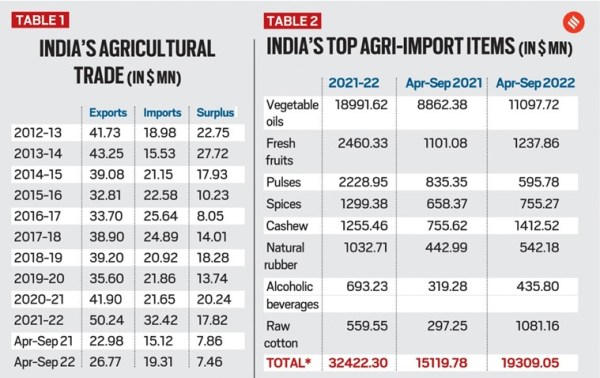

Table 1 captures trends in India’s farm products exports over the past decade. 2021-22, one can see, registered both record exports ($50.2 billion) as well as imports ($32.4 billion). The resultant surplus of $17.8 billion was much below the $27.7 billion surplus in the previous all-time-high export year of 2013-14.

The first six months of the current fiscal have seen the surplus narrow further, albeit marginally — the reason being imports grew at a faster rate (27.7%) than exports (16.5%).

The surplus in agricultural trade matters because this is one sector, apart from software services, where India has some comparative advantage.

To put things in perspective, India’s deficit in its overall merchandise trade account (exports minus imports of goods) widened from $76.25 billion in April-September 2021 to $146.55 billion in April-September this year. During the same period, the surplus in agriculture trade reduced only a tad, from $7.86 billion to $7.46 billion.

Table 3 shows India’s top agriculture export items. As many as 15 of them individually grossed more than $1 billion in revenue during 2021-22. All barring two (cotton and spices) have posted positive growth in the first half of the current fiscal too.

In cotton, not only have exports collapsed from over $1.1 billion in April-September 2021 to $436 million in April-September 2022, imports have soared from below $300 million to $1.1 billion. This has primarily been due to lower domestic production — the 2021-22 crop was estimated at just 307.05 lakh bales (of 170 kg each), as against 353 lakh bales and 365 lakh bales in the preceding two years — forcing mills to import. In the process, India has turned a net cotton importer.

Equally interesting is spices, where India’s exports in recent times have been powered mainly by chilli, mint products, oils & oleoresins, cumin, turmeric, and ginger. On the other hand, in traditional plantation spices such as pepper and cardamom, the country has become as much an importer as an exporter. India has been out-priced by Vietnam, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, and Brazil in pepper, while it has lost market share to Guatemala in cardamom.

Another traditional export item where India has largely turned an importer is cashew. In 2021-22, the country’s cashew exports were valued at $453.08 million, compared to imports of $1.26 billion. Imports have further shot up to $1.4 billion-plus during the first six months of this fiscal alone.

Table 2 shows that almost 60% of India’s total agri imports is accounted for by a single commodity: vegetable oils. Their imports were valued at a massive $19 billion in 2021-22, and imports have increased by more than 25% in the first half of this fiscal. Vegetable oils are today the country’s fifth biggest import item after petroleum, electronics, gold, and coal.

This explains two major decisions taken by the government last month. The first is the raising of the minimum support price of mustard from Rs 5,050 to Rs 5,450 per quintal for the 2022-23 crop season. This increase, over and above a similar hike last year (from Rs 4,650 to Rs 5,050), is more than that declared for wheat (from Rs 2,015 to Rs 2,125 per quintal).

The second decision has been to grant clearance (“environmental release”) for commercial cultivation of genetically modified (GM) hybrid mustard. Seed yields from the transgenic mustard DMH-11, bred by Delhi University scientists, are claimed to be 25-30% more than from currently-grown popular varieties. Besides, the “barnase-barstar” GM technology is seen as a robust platform, which can be used to develop new mustard hybrids giving higher yields than DMH-11 and with better disease-resistance or oil quality traits.

A similar approach, aimed at boosting domestic output and yields, may be required in cotton. Insect pest-resistant GM Bt technology helped nearly treble India’s cotton production from 140 lakh bales in 2000-01 to 398 lakh bales in 2013-14, and exports to peak at $4.33 billion in 2011-12.

Production has since been falling, touching a 12-year low in 2021-22, even as India has turned a net importer. It attests to the importance of focusing on domestic production and productivity, while not blocking technologies that enable these.

Tags: exports, rice, sugar, commodities, wheat, India, shipments

Read also

Ukraine exported 26 million tons of grain via the Black Sea corridor – Kubrakov

The 21st International Conference BLACK SEA GRAIN.KYIV is taking place on April 18th

In the first quarter of 2024, China reduced pork production by 0.4%

Jordan filling wheat reserves

In the new season 2024\25, Ukraine will remain the leader in the global sunflower ...

Write to us

Our manager will contact you soon