How Wheat Shortage Is Sparking a Global Food Crisis

While climate change heightens competition for the already limited resources, many non-climate stressors are also putting immense pressure on our food system. Recently, all eyes are on the wheat shortage, as experts warn it could spark a global food crisis. The world’s wheat supply is under immense pressure as the conflict in Ukraine as well as increasingly devastating weather events threaten production around the world. What sparked the issue and how are countries dealing with the shortage?

Following corn and soybeans, wheat is the third most common and widespread crop. As one of the oldest, cheapest, and most versatile grains, it remains today a critical component of food security.

This nutritious grain is essential in ensuring a sustainable global food supply for current and future generations. For centuries, wheat has been a staple ingredient not only in industrialised nations but especially in developing countries. Today, over 80% of the world’s wheat is used for flour.

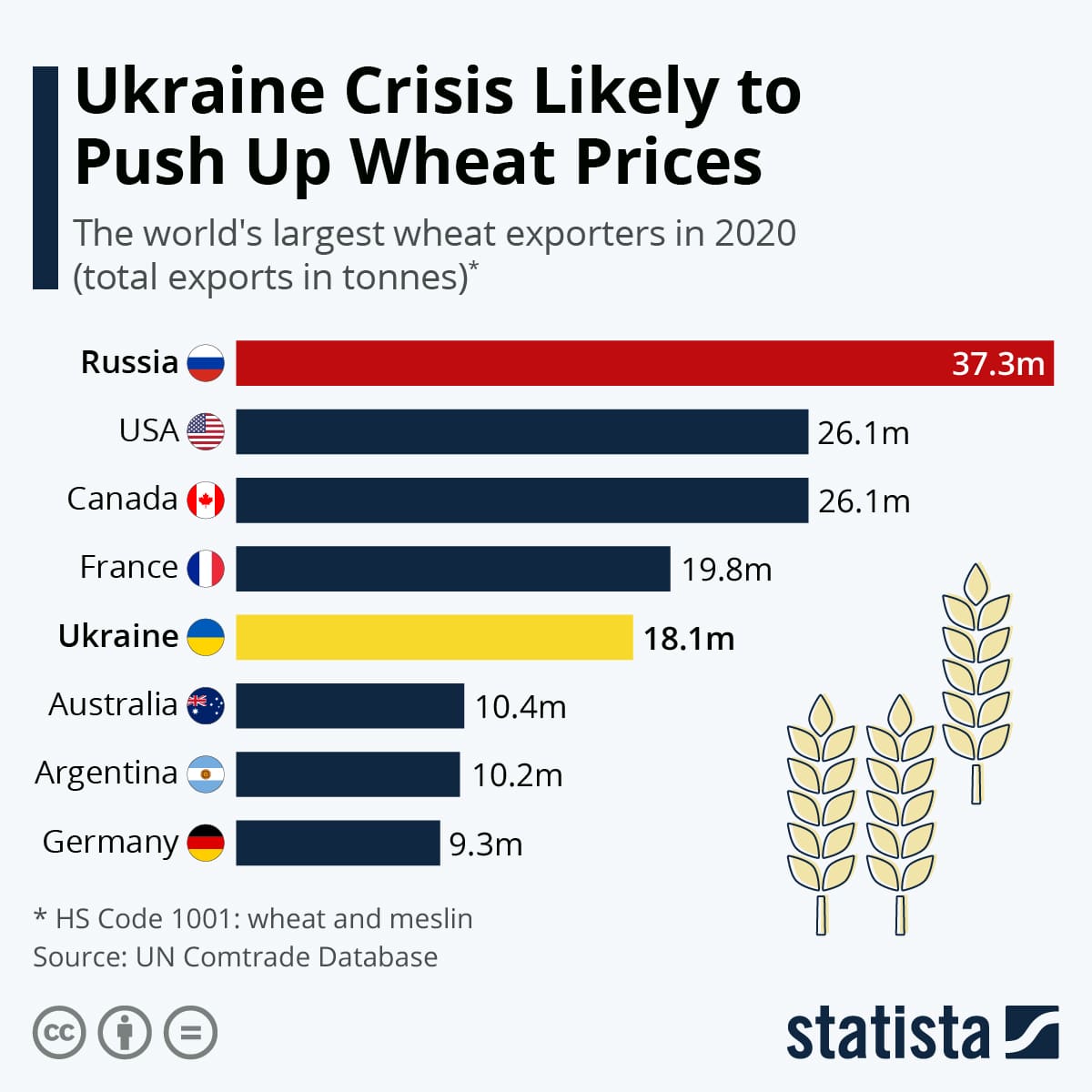

Despite being so widespread around the world, wheat production is in the hands of just a few countries. A staggering 86% of global wheat exports come from only seven countries, while just three of them hold nearly 68% of the world’s wheat reserves, with some of the world’s most vulnerable and impoverished countries relying on them for more than half of their wheat imports.

Figure 1: World’s Largest Exporters of Wheat, 2020

Both Ukraine and Russia are key players in the highly concentrated international wheat market. Described by many as the breadbaskets for much of the world, these two nations alone account for just under 30% of the world’s wheat exports. Most of the wheat they produce is sent to North Africa, the Middle East, and Asia, with countries like Egypt, Indonesia, Bangladesh, Turkey, and Yemen among the largest importers. In 2020, Russia and Ukraine also contributed 20% to the total food commodities procured by the World Food Programme, playing a key role in protecting food security in developing nations around the world.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 drastically changed the situation. Since the beginning of the war, experts have been warning about the possibility of wheat shortages. They initially feared that Ukrainian farmers might not be able to harvest all existing crops or even plant new ones this year, leading to the disruption of both local and national supply chains. However, nearly four months into the conflict, it is now clear that the impact could be much larger than anticipated and could potentially compromise wheat supplies worldwide. Indeed, while armed conflicts lead to immediate food shortages in the countries directly involved, the effects of wars on the food chain will always eventually be felt on a larger scale.

We are on the brink of a global food crisis. However, the situation we find ourselves in is more complicated than we might think. As The Atlantic writer Robinson Meyer puts it: “There isn’t a global wheat shortage. There’s a global wheat-in-the-wrong-places problem.” Indeed, Ukraine is – at least for now – still producing the grain. However, according to estimates, the destiny of more than 55 million tons of wheat – the total amount produced by Russia and Ukraine combined – is uncertain because of the ongoing conflict. And the biggest problem the war-torn country is facing is not how to produce it but how to get it out. More than 90% of Ukraine’s wheat exports make it out of the nation through the Black Sea. However, Russian soldiers have now sieged the ports, forcing the country to export its commodities by rail, barge, or truck, which, however, can only handle a small fraction of the exports in comparison to cargo ships.

As the conflict evolves and the situation becomes increasingly unstable, the world is bracing for the impact of a potential global wheat crisis. The United Nations warned that 30%- 40% of the autumn 2022 harvest in Ukraine is at risk, as farmers have been unable to plant crops. This could result in a potential loss of 19 to 34 million tons of export production this year. The consequence of a protracted war could be even more dire, with the number likely to reach up to 43 million tons, equivalent to the caloric intake of nearly 150 million people.

But there is another factor threatening wheat crops in Ukraine and Russia. Both countries combined produce approximately one-third of the world’s ammonia and potassium exports, essential ingredients in fertilisers. A shortage in these raw materials fuelled by the Ukraine-Russia conflict contributed to a price spike of nearly 30%. Sanctions on Russia have also furthered inflated energy prices, making fertilisers even costlier.

Despite having devastating consequences on the global food supply chain, the war in Ukraine is only exacerbating an issue that existed long before the country was invaded. Climate change and the Covid-19 pandemic had already heavily compromised crops worldwide over the past two years, disrupting exports, sparking a rise in food prices, and increasing poverty and hunger in the world’s least developed nations.

Climate change-related events play an increasingly crucial role in food insecurity. In summer 2021, the world faced a wheat shortage due to heatwaves and droughts that hit the US and Canada, the second and third-largest wheat exporters after Russia. Similarly, China faced the worst crop conditions ever due to climate change last year, when chart-topping rains damaged almost 30 million acres of crops and delayed planting on more than 18 million acres of land, about one-third of China’s total winter wheat acreage.

This year, the situation is even more critical and all eyes are on India. The South Asian country is currently dealing with a record-breaking heatwave that is harming food crops – with wheat yields falling by nearly half in the worst-affected areas – and heavily impacting the already precarious economy. When discussions about a potential wheat shortage amid Russia’s invasion of Ukraine began in March 2022, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced that the country would step in and seize the gap left by the war in the wheat export market. Indeed, last year India achieved record-breaking wheat production during its rabi season – which takes place in winter, usually around October and November – and it was on track for another prosperous year.

However, Modi took a step back and decided to halt wheat exports amid the long-lasting heatwave that has put the country on its knees and heavily damaged its crops. Some Indian farmers have estimated that 10% to 15% of their crops have already been irreversibly compromised by the extreme heat and future prospects do not look encouraging either. Indeed, while harvesting has just ended, the heat could compromise plants and prevent them from forming any grain at all by the time the next rabi season kicks in.

India’s decision to prioritise the domestic market by restricting exports was heavily criticised. While the country is not among the world’s largest breadbaskets, experts believe that preventing other countries from accessing its stock at a time when wheat supplies are already heavily limited only exacerbates the issue.

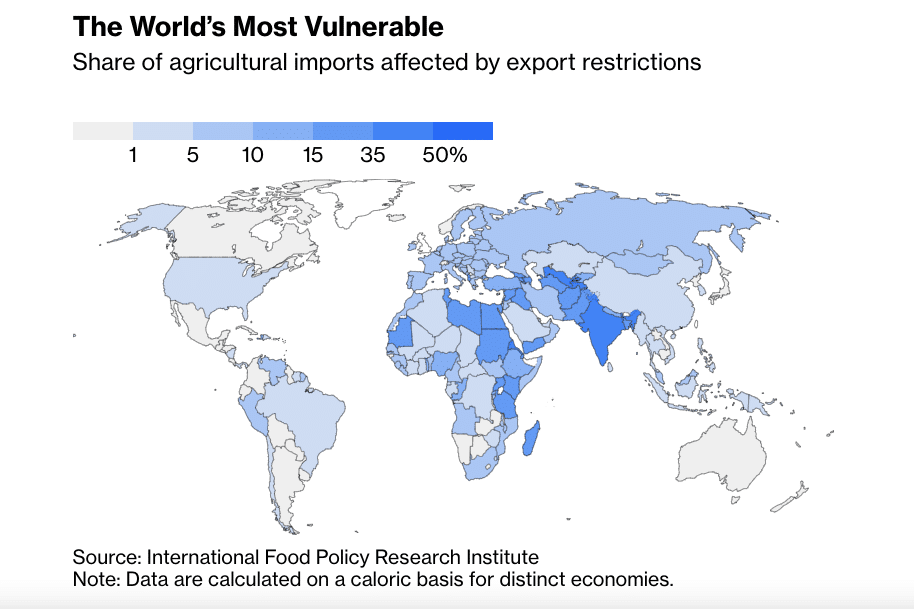

Figure 2: Countries Mostly Affected by Export Restrictions Amid Ukraine Conflict

The global supply shortage has already contributed to a spark in wheat prices, which rose 40% between February and April 2022. The economic instability and food insecurity triggered by the invasion have so far pushed 20 nations to impose restrictions on exports of wheat, maize, and other staples, covering around 17% of calories traded globally. Alongside India, Indonesia also recently imposed a ban on palm oil exports in a bid to protect domestic consumers from soaring vegetable oil prices amid the war. Yet, experts fear that such large-scale protectionism could potentially have a ripple effect and further drive up prices worldwide, fuelling poverty and hunger in the poorest countries and leading to a much-feared global food crisis which would, once again, affect those who can least afford it.

The precarious situation, combined with the effects of the coronavirus pandemic that are still largely felt around the world, could further deteriorate conditions, with the UN warning that an additional 7.6 to 13.1 million people could go hungry as the war continues, jumping from the current 276 million to more than 323 million people.

Read also

2026-2030 Economic Outlook: New Business Architecture

Middle East Tensions Are Reshaping Production Costs for Ukrainian Agriculture

Malaysia’s palm oil exports fell by 22.5% in February

Egypt plans to increase domestic wheat production

Ukraine oilseeds in 2026/27: Sowing decisions are shifting towards margin and proc...

Write to us

Our manager will contact you soon