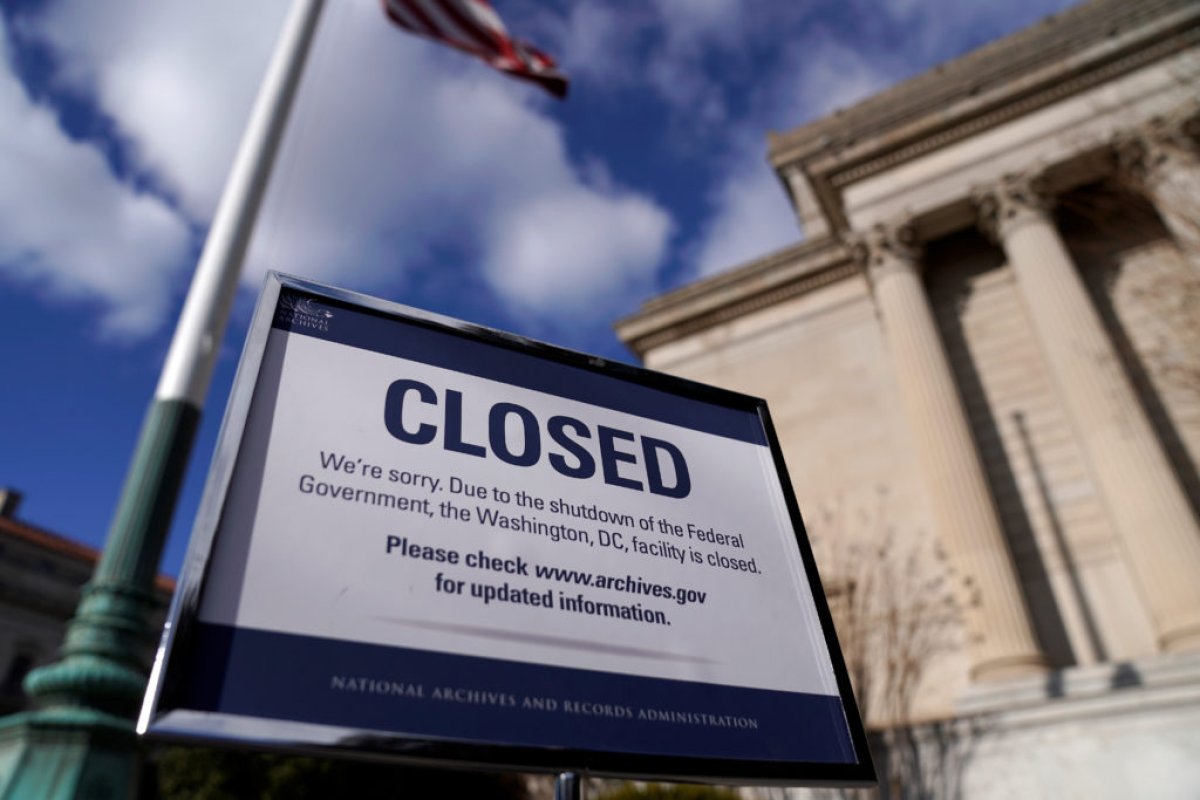

The U.S. government shutdown that began on October 1, 2025, has halted the publication of reports by the Department of Agriculture (USDA), including the key WASDE forecast that defines global supply and demand balances for grains and oilseeds. The last comparable disruption occurred during the 2019 shutdown, but the current situation is having a far greater impact, as markets are in a phase of heightened volatility. The USDA’s Economic, Statistics, and Market Information System website has stopped updating, with the latest official data dated September 28.

The absence of the October WASDE report, which was scheduled for release on October 9, has created an information vacuum at the global level. The report served as the only open source covering nearly all major agricultural markets — from North America to South Asia. Other analytical institutions, such as Rabobank, Refinitiv, Gro Intelligence, and the International Grains Council (IGC), continue to publish their own estimates, but their models focus mainly on specific regions and sectors. For their “home” markets, these models often yield accurate results; however, at the intersection of regions or for more distant markets, the margin of error rises significantly. In addition, their data is less public and harder for international traders to use efficiently.

As a result, traders are forced to rely on a limited number of private reports and local assessments, increasing the risks associated with import planning and hedging. This week alone, wheat futures in the EU and Chicago rose by 2–3%, while soybean futures jumped by nearly 4%, partly due to speculative buying driven by the lack of official data. In food-importing regions — North Africa, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia — state procurement agencies have temporarily suspended tenders, awaiting new market signals.

The shutdown has also paralyzed the work of the USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) and Farm Service Agency (FSA), which provide the raw data underlying WASDE reports. Roughly half of the USDA’s 42,000 employees have been placed on furlough, halting field data collection, crop condition monitoring, and payments under federal farm support programs. This may slow U.S. exports of corn, soybeans, and wheat in the fourth quarter, affecting global trade flows.

Analysts warn that a prolonged shutdown could have systemic consequences. Without open USDA reports, markets lose a shared informational foundation that producers, processors, and governments across dozens of countries rely on. In such conditions, even minor regional supply shifts could trigger sharp global price fluctuations.

Yet not all experts are pessimistic. As one analyst commented on the reporting freeze: “Everyone’s hooked on those reports. Once they get their fix, they start complaining it’s not good enough. They’ll survive.” Still, even if the market “survives,” participants acknowledge that the longer this information gap lasts, the harder it will become to forecast global balances — and to maintain food stability worldwide.