Why has wheat flour become so expensive in Pakistan?

For weeks now, the price of wheat flour in Pakistan has been hovering at uncomfortably high levels. Roti and naan are among the staple foods of the country, and the steep hike in the cost of flour has pinched people hard. Long queues can be seen to collect government-subsidised flour – in Mirpur Khas in Sindh, a stampede at one such distribution spot claimed the life of a 35-year-old man on January 7. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, meanwhile, has witnessed protests over the high prices.

While the central and provincial governments have blamed each other for the crisis, experts say it has been caused by long-standing deficiencies exacerbated by the Russia-Ukraine war, the devastating floods of 2022, and by the smuggling of wheat to Afghanistan.

One wheat consignment from Russia has now reached Pakistan, and some relief is expected in the weeks to come.

Flour has been selling at around Pakistani rupee (PKR) 145/kg to PKR160/kg in Punjab and Sindh, the two wheat-producing states, while the prices have been higher in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan. According to an article in Gulf News, prices of 5kg and 10kg flour bags in Pakistan “have almost doubled from a year ago”. The same article said that one naan is selling for PKR 30 while one roti is going for PKR 25 in Islamabad and Rawalpindi. 1 PKR is about .35 Indian rupee or INR.

Pakistan imports wheat to meet its consumption needs, a lot of which comes from Russia and Ukraine. For instance, in 2020, Pakistan imported $1.01 billion worth of wheat, of which the most came from Ukraine (worth $496 million), followed by Russia ($394 million), according to the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC) data. This year, the war disrupted that supply, whereas the floods of last year pulled down the domestic yield. That said, the problem in Pakistan is more of distribution than inadequate stocks.

Ammar Khan, an economy expert associated with Karandaaz Pakistan, which aims to promote financial inclusion, told The Indian Express, “Wheat prices increased largely in Sindh and Balochistan, which lost significant reserves due to the floods. The smuggling of wheat to Afghanistan is also a factor, which results in shortage locally, pushing prices higher. However, sufficient wheat stocks do exist in government warehouses. The shortage and the consequent price rise happened due to delays in distribution, which is now being addressed.”

In Pakistan, wheat is provided to mills by the provincial governments (the Indian equivalent of state governments). The mills then provide the flour to retail markets. Provinces which anticipate a shortage of wheat can request the central Pakistan Agricultural Storage and Services Corporation (Passco) warehouses for more stocks. The smaller chakkis (flour grinders), especially in rural areas, buy directly from the farmers.

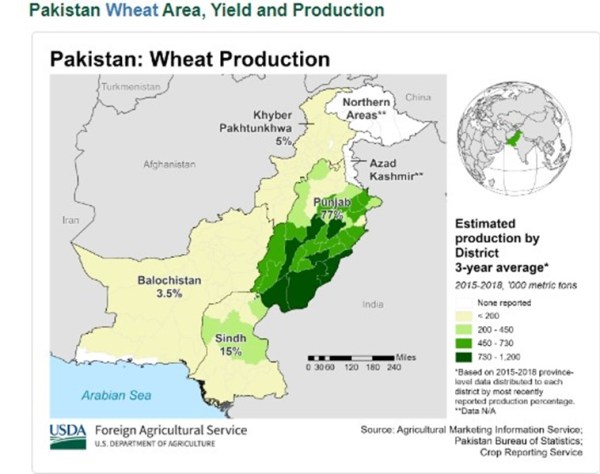

The two major wheat-producing states are Punjab and Sindh. According to the US Department of Agriculture, Punjab contributes 77 per cent of Pakistan’s wheat output, Sindh 15 per cent, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 5 per cent, while Balochistan produces 3.5 per cent. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa shares a highly porous border with Afghanistan, and a lot of wheat is smuggled across it to fetch lucrative prices in the neighbouring country. Sindh suffered heavily in the floods, which impacted its kharif crop. A report in The Express Tribune quotes The Planning Commission of Pakistan as saying that the floods damaged agriculture and its sub-sectors to the tune of Rs800 billion or $3.725 billion. As much as 72 per cent of this damage was sustained by Sindh.

Some – including the central government – have claimed that the flour shortage happened because Punjab and Sindh did not release wheat to mills on time. Others say that mill owners hoarded stocks, causing prices to climb, and the government did not act against them because many influential politicians come from rural-agrarian backgrounds. Locals also claim that mill owners are selling flour at high prices to those willing to pay, and hence not enough is available for retail stores and subsidised sale points.

Rabbi Bashir, a trader based in Lahore, said, “The party in power at the Centre is Pakistan Muslim League (N), while Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa both have Khan sahab’s [Imran Khan] government. Giving wheat to mills is the provincial government’s responsibility. A lot of the claims of shortage are just propaganda meant to embarrass the central government. Pakistan has enough wheat stock, but adequate attention has not been given to its procurement, distribution to mills, and prevention of hoarding.”

This year, the Pakistan government has announced it will import 2.6 million metric tonnes of wheat. Of this, the first 1.3 million metric tonnes have arrived, raising hopes of the prices cooling down. However, this import bill is a tight squeeze on a country staring at critically low foreign reserves. A Reuters report earlier this month said foreign reserves in Pakistan’s central bank had fallen below $5 billion, barely enough for three months of imports.

“In India, Punjab and Haryana are considered the bread baskets. Going by area alone, we should have had a bread tokra (receptacle). We should not have had to import at all,” Qalb-e-Abbas, a farmer based in Punjab’s Jhang district, told The Indian Express. “However, in Pakistan, the per acre yield of wheat is not much. There are several reasons for this. There have been no technological advancements in agriculture over the years, no high-yielding breeds developed. No land reforms either. Meanwhile, canals are drying, the water table is dipping. Diesel is very costly, power bills are high, while supply is disrupted. The farmer gets no incentives. Fertiliser is expensive, as apart from urea, others are imported and our currency is extremely devalued,” Abbas added.

A 2022 World Bank report on Pakistan’s agriculture said, “Despite considerable public spending with support from development partners, agriculture growth slowed down from an average of over 4% per year between 1970-2000 to below 3% thereafter.”

Unlike wheat, rice is among the major exports of Pakistan. This year, with the flour shortage, the demand for rice has gone up domestically.

Muhammad Zubair Latif Chaudhry, director of Siddiqia Rice Mills in Lahore and member of Rice Export Association of Pakistan, told The Indian Express, “Pakistani rice is exported around the globe, in fact, the super Basmati rice finds a mention in Waris Shah’s Heer Ranjha too. This year, floods affected the total output of rice, especially in southern Punjab, eastern Balochistan, and parts of Sindh along the river Indus. On top of it came the wheat shortage, due to which demand for broken Basmati rice has increased manifold, driving up prices.”

A report in Dawn mentioned that the cost of pulses is climbing up too. The January 13 article said the price of gram pulses had “risen to PKR 205 per kg from PKR 180 on Jan 1, 2023, and Rs170 on Dec 1, 2022.”; while masoor went to PKR 225 from PKR 200 in December. This is happening due to “the non-clearance of imported consignments at the port due to a delay in the approval of relevant documents by banks,” the article said.

Read also

Write to us

Our manager will contact you soon