Ukraine War Exposes Folly Of Anti-GMO Protectionism

The world is in a precarious place. Besides the fact that several thousand people have already been killed and millions more displaced, the war in Ukraine has triggered a trade war that could do severe damage to farmers and consumers around the world. A handful of wealthy celebrities have celebrated this development, urging the rest of us to endure skyrocketing gas and food prices “if it means putting the screws to Putin,” as Stark Trek actor George Takei so unhelpfully put it.

Comments like that play well on Twitter, but they ignore two important points everybody should recognize. Vladimir Putin won’t miss any meals because of the economic measures aimed at Russia, but lots of poor people worldwide will go hungry. If there is an upside to this war, it’s that the subsequent food price hikes and shortages have exposed the folly of Europe’s protectionist anti-GMO policies.

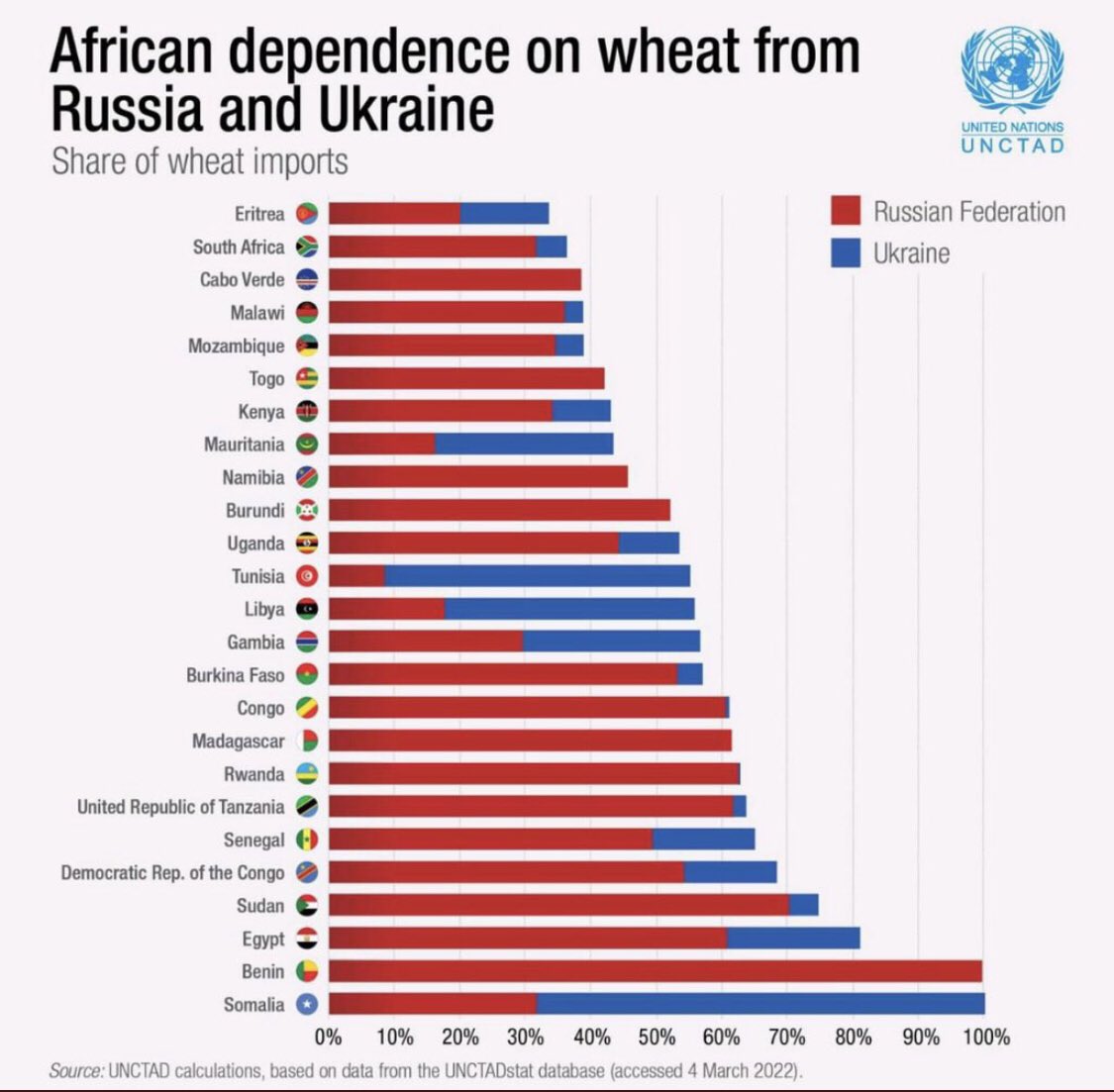

Russia and Ukraine produce just over 30 percent of the world’s wheat. Dozens of developing countries count on those exports to feed themselves, and they could suffer devastating consequences if the war and resulting economic sanctions continue to disrupt global trade.

Retired US Army Colonel Douglas MacGregor recently pointed out that the Russian army has so far avoided the center of Ukraine, where most of the country’s crops are grown. That’s important over the long term, though farmers may not be able to plant anything this year. Even if they get crops in the ground, their production will be limited because the seed, fertilizer, fuel, and other inputs they need won’t be delivered with Russian troops surrounding a major port city like Mariupol, where a lot of imported goods enter Ukraine.

This is concerning since the United Nations’ World Food Program (WFP), which helps combat food insecurity primarily in northern African countries, buys about half its wheat from Ukraine. The WFP will either have to pay higher prices to other wheat exporters or buy less grain, and that could mean “millions or potentially tens of millions more people transitioning into food insecurity,” University of Saskatchewan agricultural economist Stuart Smyth told ACSH during a recent interview.

The situation in Russia could have a similarly troubling impact. A few weeks ago, the country got skittish “about the quick pace of its grain exports to neighboring ex-Soviet countries,” Reuters reported, and moved to slow it down “to protect the domestic food market in the face of external constraints,” primarily Western sanctions.

That means higher grain prices globally, but the ensuing trade war will have further effects. Russia has slashed exports of fertilizers that growers around the world depend on. Brazil—a major exporter of soybeans, coffee, and sugar—was already having trouble acquiring all the crop nutrients it needed before the war broke out. Exacerbated shortages will likely further inflate the prices of these commodities.

And because Russia is home to large mineral deposits found in few other parts of the world, replacing the country’s fertilizer output could take several years, if it’s even possible. Argentina, another agricultural powerhouse, has capped soy and corn exports to shield its population from higher food prices in response to the fertilizer shortage, economist David Stockman noted last week. Overall, we’re talking about double-digit increases. As Olivier de Matos, director-general of CropLife Europe, wrote on March 17:

“Escalating food prices that are already plaguing consumers around the world look set to get much worse. The United Nations has warned that already record global food costs could increase by a further 22% as the war stifles international trade and decimates future harvests.”

Before Russian tanks rolled into Ukraine, The European Union was poised to implement its Farm-To-Fork program, which aimed to cut pesticide use by 50 percent and commit 25 percent of Europe’s farmland to organic food production by 2030. This was always a misguided plan; now it’s a pipe dream, and the EU knows it. Policymakers are working to relax import restrictions on transgenic (“GMO”) crops that farmers need for animal feed, an increase beyond the 30 million metric tons of genetically engineered soy Europe already imports.

This is a positive step in the grand scheme of things, and it may finally push Europe into letting farmers grow the biotech crops its regulators know pose no risk to human health or the environment. “It gives governments an opportunity to take a hard look at the underlying rationale for prohibiting GM crop cultivation in the first place,” Smyth added. “I think some governments are going to say, ‘That time has passed, and we need to change our policies.’”

Here’s to hoping the EU takes Smyth’s advice—and that this war comes to an end sooner rather than later.

Read also

Write to us

Our manager will contact you soon